Multilingual Learners

UD project addresses Delaware’s critical need for English language teachers

In Delaware’s K-12 schools, there’s no shortage of students who speak various home or heritage languages and who need specialized support as they learn to speak, read and write English.

What there is a shortage of is teachers who are specifically trained in the best ways to help these youngsters succeed. With the percentage of English learner (EL) students growing at a faster pace in Delaware than in any other state, educators say increasing the number of certified EL teachers is essential.

Now, supported by a $2.6 million federal grant, the University of Delaware’s English Language Institute (ELI) and the College of Education and Human Development (CEHD) seeks to address the problem by offering expanded opportunities to the state’s teachers and their students. Through a five-year program termed Project DELITE (Delaware English Learners’ Impact on Teacher Education), 60 teachers and 15 education paraprofessionals will be able to take the UD courses necessary to attain certification as a Teacher of English Learners or a Bilingual Teacher. The teachers will also participate in a one-year professional learning community to support each other in addressing their specific needs and building relationships with parents.

The English Language Institute in UD’s College of Arts and Sciences (CAS) has been offering the professional development program to Delaware teachers for several years, but the new funding from the U.S. Department of Education will enable a much larger number to attain certification — and at no cost to the participants.

“Delaware, which uses the term ‘multilanguage learners,’ has a critical shortage of English language teachers — both in specialist positions and in mainstream classrooms, where these students spend most of their time,” said Nigel Caplan, ELI associate professor and director of Project DELITE. “We’ve been addressing that shortage, but we wanted to find a way to increase and diversify the number of teachers we train.”

The project also has a key research component, in which information will be regularly collected from the participants to help determine what aspects of the coursework are most effective in improving their teaching and their students’ learning.

“We see this project as an opportunity not only to provide the training to an expanded group but also to assess how well all the aspects of it actually work,” Caplan said.

The project will select three cohorts of 25 applicants each and assign them to a schedule for taking the five UD courses. Each group will take classes together online, beginning during the University’s Summer Session and ending the following summer; the first cohort will begin in summer 2023, and the final one will complete the work in summer 2026. The classes offered are a collaboration between ELI and the colleges of Arts and Sciences and of Education and Human Development, with coursework covering such topics as teaching methods (in the School of Education), structure of English (Department of Linguistics and Cognitive Science) and second language testing (Department of Languages, Literatures and Cultures).

Adrian Pasquarella, associate professor in CEHD’s School of Education and co-principal investigator for Project DELITE, says that collecting data from the program’s participants is expected to show changes in their knowledge and improvements in their classroom practices when teaching English language learners. Right now, he said, EL students are taught differently in different schools and districts.

“We’re hoping that our research on the outcomes of the program will help us assess what works best,” he said. “We’d like to come up with recommendations or protocols to say, ‘This is what works, and here’s how to measure it,’ so that we can keep training teachers to make a difference in their students’ lives.”

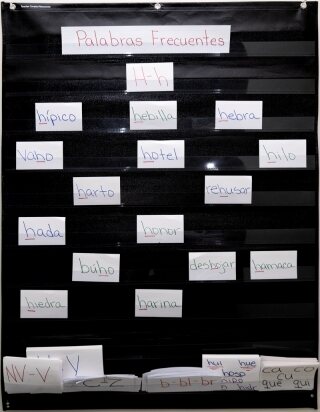

The focus in teaching EL students is on building their vocabulary, literacy and other English language skills while they retain their heritage language. The research is clear, experts say, that keeping one’s first language is an important foundation as children add fluency in a new language. Teachers don’t need to be bilingual themselves, and many will find themselves working with children who have a wide variety of heritage languages.

“As a teacher, you could walk into a classroom and have kids who speak a dozen different languages,” Caplan said. “These children have the ability to become truly multilingual and multiliterate, and that’s an asset for them. We need teachers who know how to support students as they do this.”

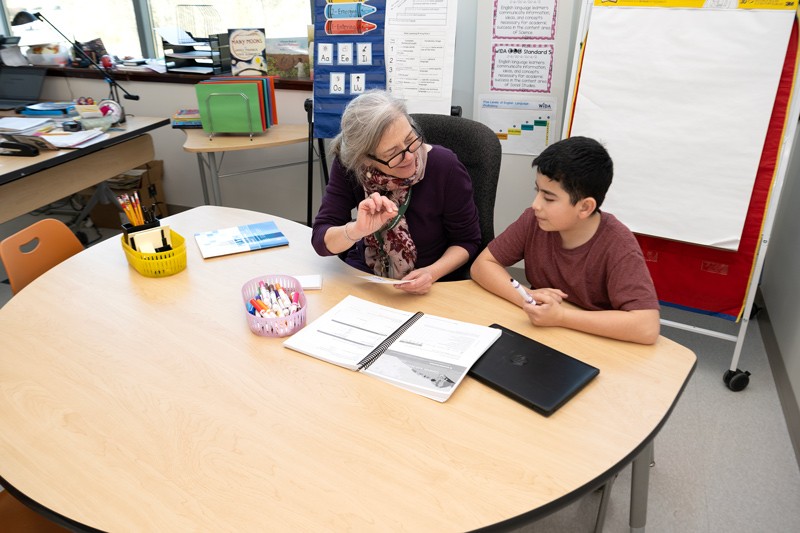

Two experienced classroom teachers who are completing the same UD certification coursework that Project DELITE participants will take added that the classes have helped them enhance their teaching skills as they work with EL students. They both say they’d encourage other teachers to make use of the program.

“The classes really focus on practical skills you can use in the classroom,” said Tory Curtis, who teaches K-5 EL students at William F. Cooke Jr. Elementary School in Hockessin, a public school in the Red Clay Consolidated district. “This program would benefit any teacher, not just specialists, because we’re all going to have English language learners in our classrooms.”

She said she uses techniques she’s learned in the program as she works with EL students who spend most of their school day in mainstream classes, with lessons taught in English, and leave the classroom periodically for individualized language instruction — a system followed in many Delaware schools. Curtis focuses on reading skills with her youngest students and broader academic skills with older ones, always building on the foundation of their first language.

For teacher Maggi McNutt, becoming a certified EL educator is key to her role at Academia Antonia Alonso Charter School, a dual-language immersion school in which all children in grades K-5 take half their classes English and half in Spanish. With an especially large number of EL students, the school’s philosophy emphasizes its appreciation for the first-language knowledge that children and families bring to class.

McNutt said the learning strategies taught in the UD classes have been practical and helpful.

“Using a lot of visuals, being responsive, increasing your oral interaction with children, these are all techniques that can be used by all teachers,” she said. “I think it promotes the exchange of ideas, which is very beneficial for everyone.”

More about Project DELITE

In line with the mission of both CAS and CEHD, the project will help with the teacher shortage in this high-need area and foster equitable, inclusive teaching.

Teachers and paraprofessionals who take part in Project DELITE will take the sequence of five UD courses online, giving access to educators throughout Delaware. After the classes are completed, the project will offer participants an additional year of professional development in which they can meet regularly and share experiences with one another.

The grant for the program was awarded by the U.S. Department of Education Office of English Language Acquisition’s National Professional Development Program.

According to the most recent federal data, about 5 million, or 10.4% of the nation’s K-12 students, are English language learners. Delaware, where just over 11% of students are in this category, is among the 10 states with the highest proportion. In addition, the percentage increase in Delaware’s EL student population in recent years leads the nation.

EL students in the state speak a variety of languages at home; the largest number speak Spanish, followed by those who speak Haitian Creole and almost 100 other languages.

Regardless of their language backgrounds and academic challenges, children benefit enormously from support by trained EL teachers, Pasquarella said.

“Some children who are English language learners struggle with classroom work as they’re becoming multilingual, and there’s a gap that’s made worse by poverty,” he said. “But some of them go through the educational system, do very well and graduate at the top of their class. We want to figure out how teachers can make that happen.”

Read this story on UDaily.

Photos by Kathy F. Atkinson.