Creating improved observational protocol for writing instruction

With the attention that the Common Core State Standards give to writing, and the writing requirements in the new Smarter Balanced Assessments, many teachers and administrators are concerned about their approach to writing instruction.

“As an elementary principal, and later, as Director of Curriculum and Instruction, I frequently observed primary level teachers during the English Language Arts block. It was rare to observe writing beyond sentence completion, yet alone the authentic, rigorous writing of the CCSS,” said Alexandra Neal, retired director of curriculum and instruction in Colonial School District. “My teachers would tell me that they needed more professional development because many felt that their training was so focused on teaching students how to read that writing was not prioritized.”

School of Education literacy researchers have recognized this need for effective writing pedagogy. David Coker (PI), Elizabeth Farley-Ripple, and Charles MacArthur are beginning the final year of a $1.4 million grant from the Institute of Education Sciences titled “Investigating the Impact of Classroom Instruction and Literacy Skills on Writing Achievement in First Grade.” Through the observation of 50 first-grade classrooms in Delaware, the research team aims to analyze writing instruction, determine the best methods for instruction, and link teaching to student achievement. (See 2011 UDaily article for more detail.)

See results in JANUARY 2018, Journal of Educational Psychology, The Type of Writing Instruction and Practice Matters: The Direct and Indirect Effects of Writing Instruction and Student Practice on Reading Achievement

Developing an observational protocol

In a long-term effort to produce a useful writing curriculum, the research team first developed a sophisticated observational protocol to learn about writing instruction in the classroom.

Many researchers gather this information through teacher surveys, which give a general understanding of teaching methods. However, these surveys are often limited in the type of information that they can provide. For example, surveys may not accurately capture variations in instructional methods or the amount of time devoted to each activity. By contrast, observations can provide a clearer understanding of the complex interactions that occur during a lesson, including how classroom management, student autonomy and variations in instructional approach may affect teaching and learning.

Recognizing reading and writing as interrelated activities, Coker and his team developed an observational system that would capture instructional foci, classroom dynamics and student behavior.

They established 9 reading codes, such as “comprehension” and “vocabulary,” and 16 writing codes including “editing,” “prewriting,” and “handwriting.” The system also recognized 111 individual codes related to the grouping of students, the management and level of instruction, materials used, and whether the activity was teacher or student-led.

To capture student behavior, the team developed a code called the “Nature of Student Activity,” which included behaviors like “written response” or “oral response” and language-level options like “individual words” or “individual letters.”

Questions they were looking to answer included:

- What types of writing, reading, and oral language instruction was happening?

- How much of each type of instruction was occurring?

- Were there transitions between lessons as students move from one subject to another?

“We’re interested in the broad literary focus in the first-grade classroom,” said Coker. “To make sure that our observational system could address these questions, we spent some time testing early versions of this protocol in the classroom to see if teachers were doing what we expected. We had to add several codes because they were doing things that we didn’t anticipate.”

Developing new educational technology

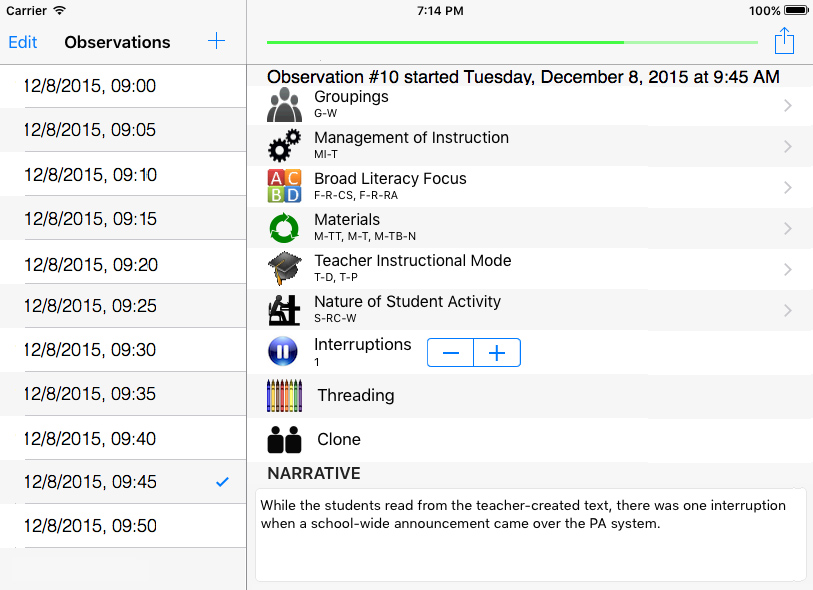

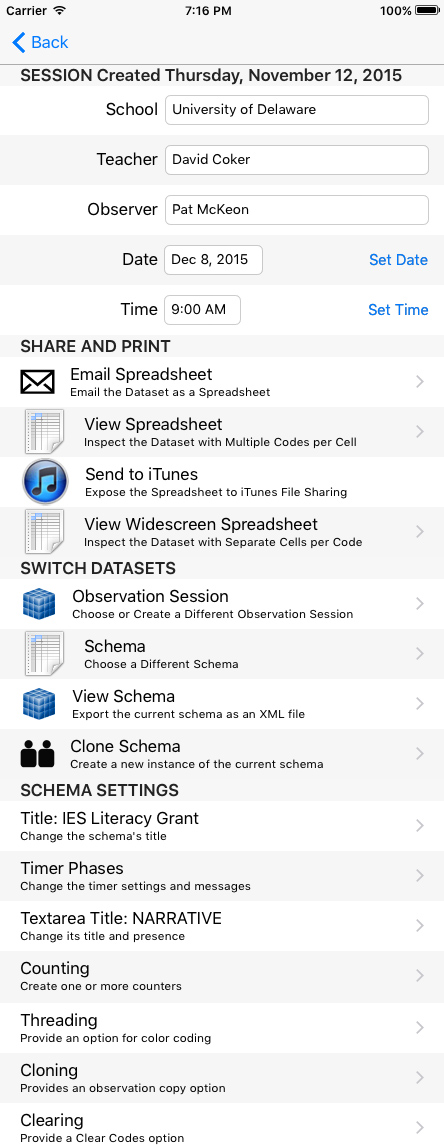

After testing and revising their coding manuals, the research team worked with Fred Hofstetter, professor of educational technology in the School of Education, to develop iSeeNcode, an iPad application. iSeeNcode facilitated data collection for the researchers and their observers, a team of retired teachers including Joanne Deshon, Sharon Meconi, Jeanne Moore, Alexandra Neal and Patricia McKeon.

The app replaced paper coding methods by allowing users to log their observations digitally. The app also included brief, easily accessible descriptions of each code, eliminating the need for hard-copy reference material. As observers entered codes, the app imported data into a spreadsheet, which could then be easily exported for analysis.

“Most of the controls were based on the codes developed by Coker and his team, but the app also let the observers make open-ended comments about what they were seeing,” said Hofstetter. “Color coding was used to keep track of common threads through the observations, which were made in five-minute intervals with a timer showing the observers how much time remained for each observation. The app also had a counter that the observers could use to count interruptions.”

Though iSeeNcode was initially designed for this literacy project, it is now available as an app to support observation-based research across disciplines. See a tutorial or download the iSeeNcode app through the Apple Store for iPads and iPhones.

Surprising observational results

Coker and his research team found that teachers on average spent about 27 minutes a day on writing instruction. These results accorded with their expectations, since nearly all of the observed schools scheduled half an hour a day for writing instruction. Most of this instruction centered on developing skills or process writing and was organized in whole-class settings with teachers presenting information or asking students questions.

The team was surprised, however, in the amount of variability around the average time per day, which reveals how much individual classrooms or teachers differ from one another. The team found that many teachers allocated much more or less time than the average. Per teacher, the amount of time ranged from about 6 to 74 minutes.

“In some classrooms, there was no writing instruction and that’s the part that blew us away,” said Coker. “We observed 18 out of 200 entire school days across 4 different waves where we saw zero writing instruction–that’s almost 10%.”

The full observational results of this study will soon be published in a special issue of Reading and Writing devoted to writing instruction around the world. An advance online version of this article, “Writing instruction in first grade: an observational study,” is available here.

Next steps

Coker and his team are continuing to analyze their observational data. As the project moves forward in its final year, the team anticipates identifying how specific features of first-grade instruction in reading and writing are related to students’ writing achievement.

iSeeNcode, now generalizable for other research projects, is expected to be available for download through the Apple Store for iPads and iPhones in 2016.

Related references

Baker, S. K., Gersten, R., Haager, D., & Dingle, M. (2006). Teaching practice and the reading growth of first-grade English learners: Validation of an observation instrument. The Elementary School Journal, 107(2), 199-219.

Bitter, C., O’Day, J., Gubbins, P., & Socias, M. (2009). What works to improve student literacy achievement? An examination of instructional practices in a balanced literacy approach. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 14(1), 17-44.

Bohn, C. M., Roehrig, A. D., & Pressley, M. (2004). The first days of school in the classrooms of two more effective and four less effective primary-grades teachers. Elementary School Journal. 104 (4), 269.

Coker, D. L. Jr., Farley-Ripple, E., Jackson, A., Wen, H., MacArthur, C. A., & Jennings, A. S. (2015). Writing instruction in first grade: an observational study. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, Advance online publication. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-015-9596-6.

Connor, C. M., Morrison, F. J., Fishman, B., Ponitz, C. C., Glasney, S., Underwood, P. S., et al. (2009). The ISI classroom observation system: Examining the literacy instruction provided to individual students. Educational Researcher, 38(2), 85-99.

Cutler, L., & Graham, S. (2008). Primary grade writing instruction: A national survey. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(4), 907-919.

Graham, S., Harris, K. R., Fink-Chorzempa, B., & MacArthur, C. A. (2003). Primary grade teachers’ instructional adaptations for struggling writers: A national survey. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95, 279-292.

Taylor, B. M., Pearson, P. D., Peterson, D. S., & Rodriguez, M. C. (2003). Reading growth in high-poverty classrooms: The influence of teacher practices that encourage cognitive engagement in literacy learning. The Elementary School Journal, 104(4), 3-28.

Wharton-McDonald, R., Pressley, M., & Hampston, J. M. (1998). Literacy instruction in nine first-grade classrooms: Teacher characteristics and student achievement. Elementary School Journal, 99(2), 101-128.